Photo: Remote learning

By: Jamal Saeh, Maysoun Shomali, Kelly Chiu

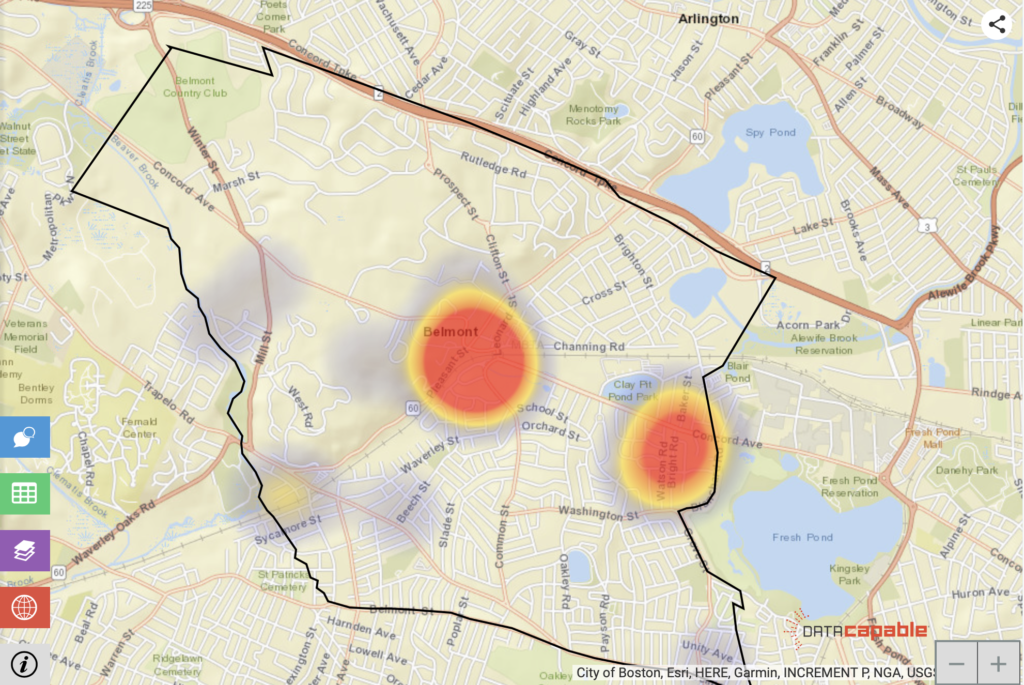

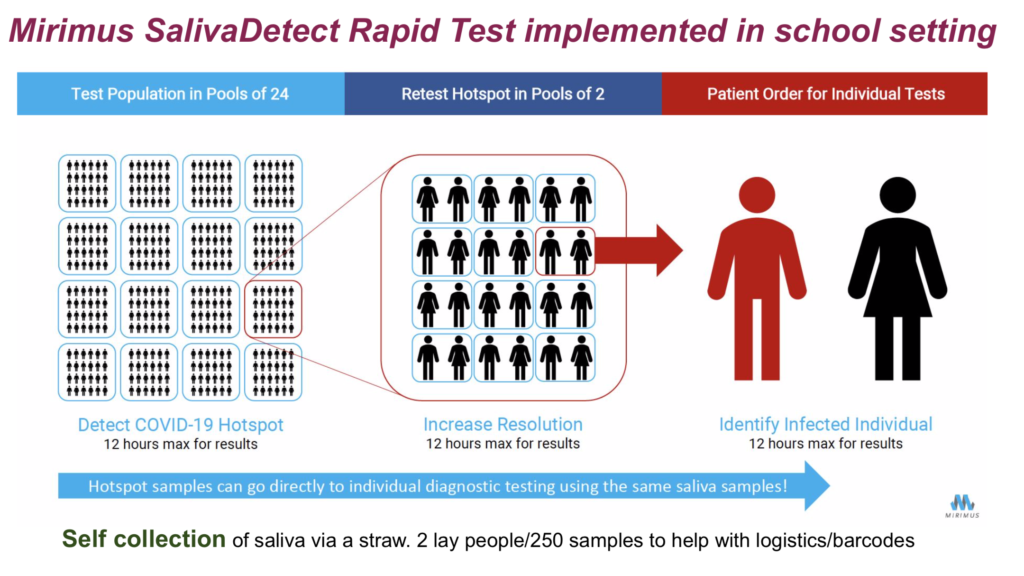

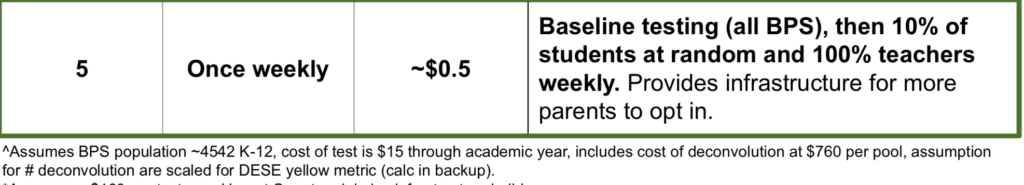

Advocates for reopening schools believe that Belmont is ready to open school per the Department of Elementary & Secondary Education guidance. The majority of Belmont parents voted for the hybrid model. A number of us have worked on solutions to improve the air circulation in Belmont school buildings, and proposed strategies for surveillance testing, and daily symptom reporting & temperature checks as tools to further reduce the risk of coronavirus infection for students and staff.

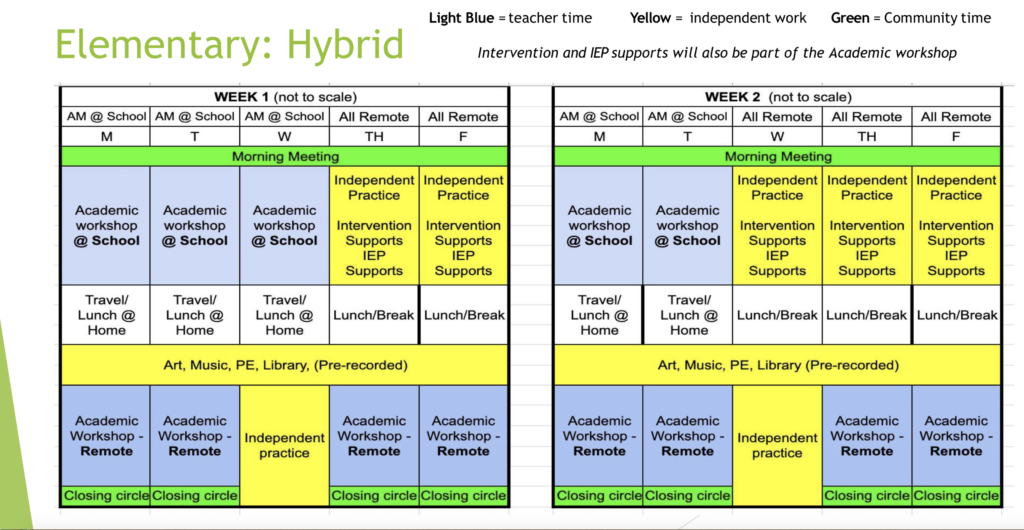

Public schools should provide remote learning as an option for those families who have risk factors requiring them to keep their children at home. It must not however limit the opportunities for the rest of the Belmont community who, in trusting the experts, believe that what is best for their families is a meaningful return to school. Similarly, remote learning cannot become the default option through measures that handicap the hybrid models, limiting in-person instructional time to six hour a week despite having initiatives like surveillance testing that can help increase the number of hours students can safely spend with their teachers and peers. Advocates for remote learning say “remote is an extreme action to an extreme situation;” we say solutions built on extreme fear beget extreme policies, and are rarely effective.

The Boston Globe reported on how state emergency child care centers managed the COVID-19 infection risks. By following the state guided risk mitigation countermeasures, only nine out of the 550 centers had more than a single infection between March and May 2020. Remarkably, this was both during a time when the state was practically in lockdown, and at centers that were catering to children of essential workers, who are perceived to be at the highest risk of infection. This good news suggests that the state guided risk mitigation plans enable the safe reopening of Belmont schools.

A recent publication in Science questioned the effectiveness of school closures. Researchers observed that “given the near universal closing of schools in conjunction with other lockdown measures, it has been difficult to determine what benefit, if any, closing schools have over other interventions.” Further, they conclude “[t]here is now an evidence base on which to make decisions, and school closure should be undertaken with trepidation given the indirect harms that they incur. Pandemic mitigation measures that affect children’s wellbeing should only happen if evidence exists that they help because there is plenty of evidence that they do harm.”

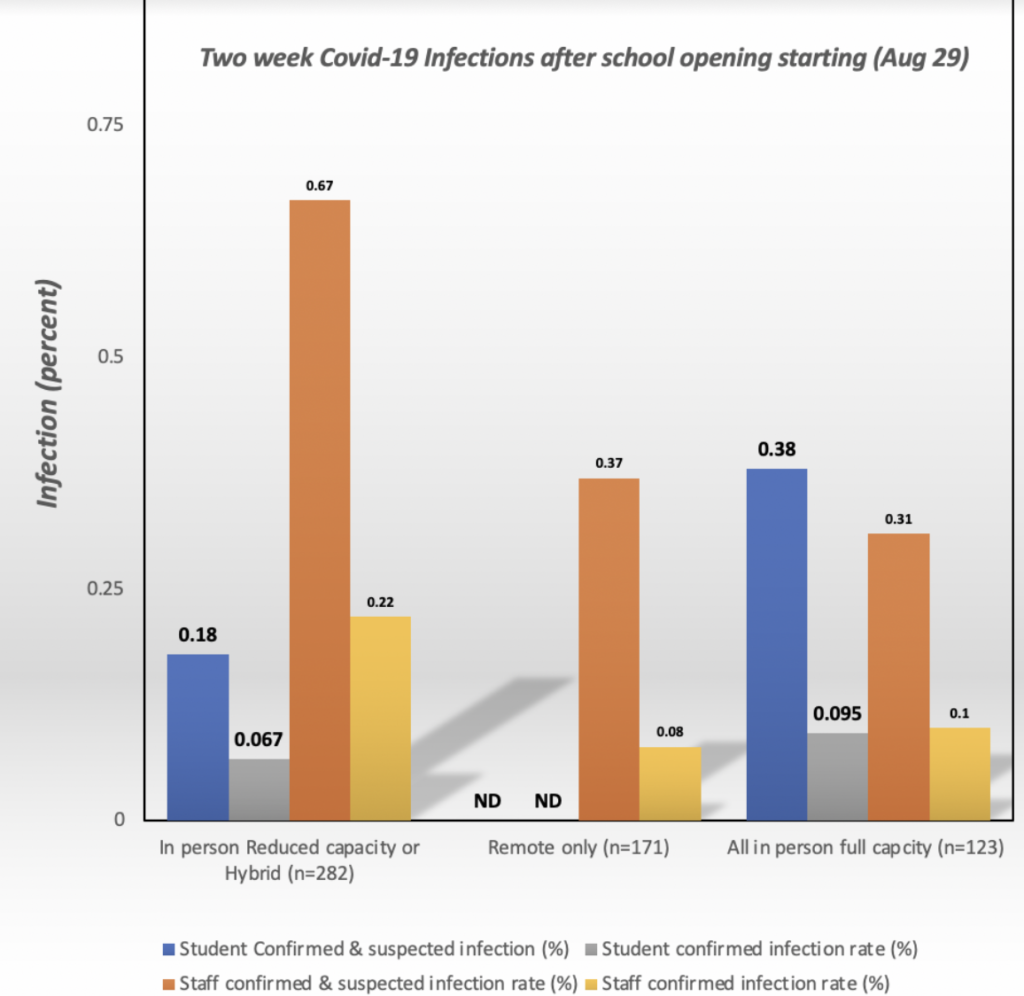

Some claim that remote learning options are the safest option for families and teachers, but what does the evidence tell us? Scientists at Stanford University analyzed real-world-evidence of Covid-19 infections after schools reopened around the country. Data collected over a two week period from 598 schools in 46 states, 353,311 students, and 41,628 staff show that the risk of infection to students and teachers is low across all school opening plans. The data were reported by 64% of public schools, the rest were by private or independent schools. To a large degree, the mitigation plans implemented in these schools were similar to Belmont Public Schools (BPS). Mitigation strategies reported included less than 90 percent of students and staff masking, 79 percent of schools reported increased ventilation and 72 percent reported cohorting. Only 8 percent of schools had staff tested before the start of school. The summary in Figure 1 shows that the risk to teachers and students are not too dissimilar across models. The suspected and confirmed COVID-19 infections among staff in Remote and “All In Person Full Capacity” was 0.37 percent and 0.31 percent respectively. Said differently, staying at home does not appear to reduce the staff risk of infection to zero and is likely similar to the risk of going to school in person. Risk mitigation measures at schools are effective in reducing the risk. Further, it suggests that children are not vectors of community infection, consistent with a body of evidence that indicates that infection rate in K-12 schools reflects the prevalence in the community. This is reassuring data and supports the reopening of Belmont schools. It also invites the Belmont School Committee, the administration and the community to examine other risks and issues specific to the remote learning model.

It will take years to fully assess the impact of remote learning on children’s emotional and physical wellbeing. The American Academy of Pediatrics led a push for students to be physically present in classrooms rather than continue in remote learning and was reflected in the CDC recommendation. A CDC report revealed that as of late June 2020, anxiety disorders had tripled compared to 2019. A survey of case studies in local hospitals and schools suggest that “Boston has a looming public health crisis” and that “children are not OK”. There is published data that support the AAP position to send kids back to school. One study showed the risk of depression and suicide in children decreased when schools reopened. Another study showed that during quarantine, home had become more dangerous than schools. More domestic accidents were reported requiring emergency visits, with a higher incidence of accidents than in the previous three years. With the Covid-19 infection risk being so low to both children and teachers, the school committee and the administration must confront how their school opening plans are compromising the mission of public education.

It is important that we reflect on less technocratic critiques of remote learning that are fundamental to our aspirations as a public school system and a country. Remote learning rewards the economically privileged and disadvantages the rest, particularly people of color. Consider the solutions that are at the disposal of those more able to manage the negative aspects of remote learning: the formation of “pandemic pods,” hiring professionals to quarterback their children’s remote education, and staying at home to supervise their children’s learning are just a few examples. While we may want to consider these as personal and benign in nature, they exclude the people that public education was designed to support, and worse, have the potential to perpetuate racial inequities. In an era when, rightly, Belmont Public Schools has championed a focus on equity and restorative justice, we must consider the placement of remote learning in the troubled history of public schooling in this country: It is part of a continuum of “white flight” that weakens public schools and presents obstacles to integration efforts and equity.

By choosing hybrid, Belmont is saying we’re better than this.

Jamal Saeh, PhD is the Executive Director and Global Program Leader in early clinical oncology group at Astrazeneca. He is a Belmont parent to two Belmont High students.

Maysoun Shomali is a principal scientist and lab head at Sanofi. She is a Belmont parent to two kids in the public schools.

Kelly Chiu, MD FAAP is Assistant in Medicine, Division of General Pediatrics and Instructor in Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School. She is a parent to two school aged kids.