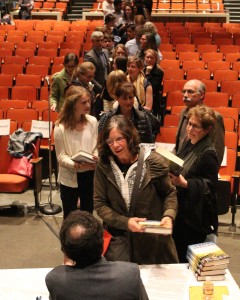

Photo: Nick Kristof.

Nicholas Kristof recalled a story about a friend who came home to the US from a year helping refugees in Darfur, the area of western Sudan still suffering the humanitarian after effects of a decade-long war.

“She comes back over Christmas vacation, she’s in her grandmother’s backyard and totally loses it, weeping with abandon,” Kristof told the audience attending his talk on “A Path Appears: Transforming Lives, Creating Opportunities,” the bestseller written by him and his wife, Sheryl WuDunn.

What caused his friend’s sudden reaction was seeing a bird feeder hanging close by.

“She was thinking about all the things she saw in Darfur and thought how incredibly lucky she was,” growing up in a country where the basic necessities; housing, ample food, clothing, and security is taken for granted, so much so that there remains enough “to help wild birds get through the winter,” he said at the talk sponsored by a new community group seeking to build on the book’s theme of creating a better world.

“And I do think that, in the same sense, the fact that we are here in Belmont, means we have won the lottery of life,” the New York Times columnist told attendees in the Belmont High School Auditorium on Wednesday, April 15.

And by being in that fortunate state, “there are obligations that come with it;” of demonstrating compassion, empathy, and dignity to those who are burdened by poverty and circumstance.

Kristof’s talk came as A Path Appears in Belmont, the community group using the book’s themes to decide on a town-wide project “on how can we make a difference,” said Jackie Neel of First Church, Belmont’s Social Action/Human Rights subcommittee and who started and now spearheads the effort beginning last year.

After reading the book, “it was as if a spark had gone off in my head, and it has certainly exploded this evening,” Neel said to the nearly full hall.

After several months of events and discussions, the three areas of concern for a possible “call to action” by the group in the fall are hunger, homelessness, and human sex trafficking, said Neel.

Before introducing Kristof, Neel invited State Sen. Will Brownsberger and four Belmont High students to the lectern.

For Olivia Cronin, Maggie O’Brien, Ritika Sexena and Rose Carlson, the event was an opportunity to introduce A Path Appears’ effort by students to expand on last year’s success in creating a garden at the High School providing fresh produce to the Belmont Food Pantry.

Rose Carlson (left, head turned), Olivia Cronin, Ritika Sexena (white dress) and Maggie O’Brien of Belmont High School.

“We want to connect Kristof’s ideas of change and put that in our community and we decided to focus on food and gardening as achieving that,” O’Brien told the Belmontonian before the talk.

The program will expand on last year’s model to include a multi-generational component, involving the elementary schools and the Belmont Senior Center, “connecting gardens around town and trying to use it to change our educational system and achieving awareness about food insecurity and having cooking classes, all done to make a difference,” said O’Brien.

Kristof’s journey from a journalist focused on international reporting – he won his first Pulitzer Prize (with his wife) in 1990 on China’s mass movement for democracy and its subsequent suppression – to writing about humans in crisis when he traveled to Cambodia in the late-1990s to write about child prostitution. There he came across pre-teenaged girls in a house waiting to be sold for sex, “just like slaves from the 19th century. That haunts me.”

“So it’s hard to go from that to writing about exchange rates,” he said.

He later returned to “buy” two girls from the brothel and brought them back to their families.

“In each case … I got a written receipt,” he said. “When you get a written receipt in the 21st century, you know that that is profoundly wrong.”

“That’s why I got engaged, because of the people I met,” Kristof said. People such as the Ethiopian 14-year-old, who crawled 30 miles to obtain surgery after childbirth who then worked her way to became a nurse at the hospital.

“It’s kind of a reminder that we’re talking about is not just a personal tragedy, but also real opportunities to empower people, to serve themselves and their families,” said Kristof.

Kristof believes that part of the reason both philanthropies – which Kristof said is undergoing a revolution in seeking facts on backing initiatives – and government policy are not as effective as they can be is due, in part, to “an empathy gap.”

He noted the wealthiest families donate half as a percentage of its income than poorer families to charities. It’s not that they rich are less caring, said Kristof, but rather the affluent “are more isolated from need;” living in an upscale neighborhood with reasonably well-off residents.

“You are aware of disadvantage need but it’s more of an intellectual awareness, while in contrast, if you are poor in America today, everyday you encounter people who are truly are in need so when you encounter that, you reach into your pocket to respond,” said Kristof.

“More and more, I think this empathy gap is one of the real barriers towards making a difference,” he said.

To break this cycle, people should “get out of your comfort zone,” whether it is committing yourself to public service, travel or, for students, taking a gap year between high school and college. That should not be exclusively helping with need overseas as there is much to do in the US such as teaching literacy or working with those incarcerated.

State Sen. Will Brownsberger (left) with New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof.

“But whatever you find works … will be a real part of your education and to chip away at the empathy gap,” he said.

Kristof ended the night answering a question from a woman who spent the past year working in Rwanda, who noticed how many aid workers were caught up in the “white savior” complex, coming of means to provide, without empathy, what their own government or people can not.

Kristof said everyone “should show dignity … and do a lot more listening” when going to assist people.

But he thought it would be a real misfortune if American were to back away from helping because of the fear of offending.

“Right now, the basic problem is not that too many people want to help Africa; it’s not enough,” he said.

“Acknowledging that helping people is hard. And the challenge is to find a way to pay some of that back.”